Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer’s disease: Increasing evidence for a major role of the virus

The concept of a viral role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), specifically of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1), was first proposed several decades ago (Ball, 1982; Gannicliffe et al., 1986). Legitimizing the concept clearly depended on a positive answer to a number of test questions, the first of which was whether or not HSV1 is ever present in human brain. The subsequent discovery that HSV1 DNA resides in a high proportion of brains of elderly people in latent form (Jamieson et al., 1991)—both normals and AD patients—immediately made the concept more credible, but raised associated questions such as whether or not the virus is ever active in brain or is merely a passive resident there; whether on its own it is a causative factor in AD or it acts thus only with another factor, perhaps genetic; if active, what causes its activity; whether there is any link with the characteristic abnormal features of AD brains or their components, and whether, if indeed implicated in AD, antiviral agents would be useful for treating the disease. These questions were posed in a previous review (Wozniak and Itzhaki, 2010)—and strong evidence was presented that permitted the answer to each question to be “yes” or, very likely to be “yes”. The present review briefly summarizes the earlier evidence, and provides an update, which is especially timely in view of the subsequent steady increase in number of relevant publications.

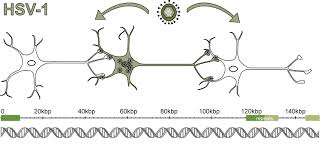

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1), when present in brain of carriers of the type 4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE), has been implicated as a major factor in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). It is proposed that virus is normally latent in many elderly brains but reactivates periodically (as in the peripheral nervous system) under certain conditions, for example stress, immunosuppression, and peripheral infection, causing cumulative damage and eventually development of AD.

Diverse approaches have provided data that explicitly support, directly or indirectly, these concepts. Several have confirmed HSV1 DNA presence in human brains, and the HSV1-APOE-ε4 association in AD. Further, studies on HSV1-infected APOE-transgenic mice have shown that APOE-e4 animals display a greater potential for viral damage. Reactivated HSV1 can cause direct and inflammatory damage, probably involving increased formation of beta amyloid (Aβ) and of AD-like tau (P-tau)—changes found to occur in HSV1-infected cell cultures.

Implicating HSV1 further in AD is the discovery that HSV1 DNA is specifically localized in amyloid plaques in AD. Other relevant, harmful effects of infection include the following: dynamic interactions between HSV1 and amyloid precursor protein (APP), which would affect both viral and APP transport; induction of toll-like receptors (TLRs) in HSV1-infected astrocyte cultures, which has been linked to the likely effects of reactivation of the virus in brain.

Several epidemiological studies have now shown, using serological data, an association between systemic infections and cognitive decline, with HSV1 particularly implicated. Genetic studies too have linked various pathways in AD with those occurring on HSV1 infection. In relation to the potential usage of antivirals to treat AD patients, acyclovir (ACV) is effective in reducing HSV1-induced AD-like changes in cell cultures, and valacyclovir, the bioactive form of ACV, might be most effective if combined with an antiviral that acts by a different mechanism, such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

Source: journal.frontiersin.org

See on Scoop.it – Virology and Bioinformatics from Virology.ca